The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

Page 52: A Lighter Moment in a Heavy Place, and a Deep Dive into the Canister Hoisting System.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

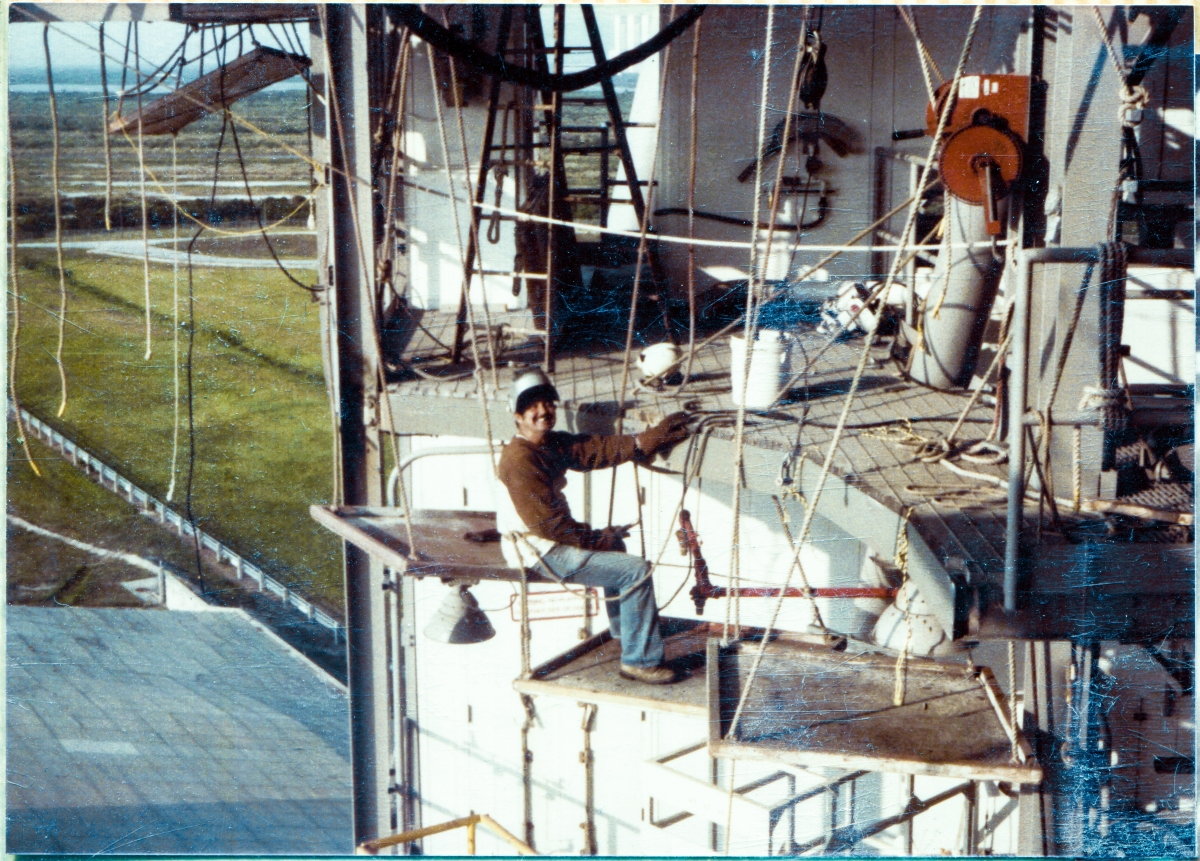

My incomplete case of prosopagnosia means that some of the time (but not all that often, and it's infuriatingly random in all instances), faces will be perfectly recognizable to me, and I won't have the least trouble with it, and in the case of the photograph above, we're getting a sterling example of that very thing, and the person you're seeing here across a yawning gulf of forty years is Dave Skinner, and of that there can be no doubt whatsoever, because... incomplete prosopagnosia.

Maybe ask Oliver Sacks how it works, ok? I sure as hell don't know. Nor do I suppose myself to know, either. Oliver's prosopagnosia came with topographical agnosia, but mine does not, and in fact, as you may have already discovered, following me around via the photographs through the labyrinthine twists and turns of the launch pad, I am lethally accurate with what I call my "nav skills" and I'll navigate you under the table and down into a hole in the ground if you ever foolishly choose to go up against me with it, so each instance is different and right there is where we'll give the matter a rest, ok?

Dave was a Union Ironworker out of the Local 808 Union Hall, and worked for Ivey Steel. He had a brother Steve, and the both of them were regular fixtures on the Pad while I was also working for Ivey Steel, and we will be seeing both of them again, more than once, in the coming photographs.

In our photograph, it's early morning, and Dave has spotted me across the way at the 125'-0" level of the RSS, and is indulging himself in a bit of whimsy, mugging for the camera, before pulling his hood back down and continuing with the work of modifying the 125' Floor Steel at the Orbiter Mold Line (I still can't decide if that's a welding stinger Dave's holding in his right hand, or a cutting torch, and one of the ropes holding up one of the floats is in exactly the wrong position to allow me to say, one way or the other, with enough confidence), in preparation for the installation of the OMS Pod Heated Purge covers, which were a nightmare, and which we will be hearing a LOT more about, soon.

But before we launch off into those very deep and very dark woods, let's stop and consider what's holding Dave up. What's keeping him from falling to his death.

The floats.

This is probably the best picture in the entire series, for depicting the kind of floats that Union Ironworkers were in the habit of using, back in the mid 1980's.

Nowadays, the Safety Man would shut the whole job down if he saw somebody perched above certain death in this manner, and even though I've been out of touch with all of the practitioners of the craft I used to work with for a pretty good while now, my guess is that, right now, most of the veteran ironworkers you might encounter on a job would rather be doing it the way you see it being done in this photograph, instead of what's being forced on them today.

People freak out when they see this stuff.

Wait a minute, let me correct that.

People who do not know, freak out when they see this stuff.

People who, in their entire lives have never been within shooting distance of something like this, and who would recoil in terror if asked to get out there on the damn thing and use it, will invariably stand there, look you squarely in the eyes with the most sober expression on their faces that you could imagine, and then proceed to tell you how to DO it, even though they have no idea whatsoever as to what the hell they're talking about. No idea at all. None.

Union Ironworkers KNOW.

They know what works.

And they know WHY it works.

And a surprising amount of why has nothing whatsoever to do with the actual, as-it's-being-used functionality of the thing, but instead revolves around setting it up, and getting it into position, coupled with the real-world realities of EXACTLY how safe it is, and whether or not that safety can be, real-world, improved by doing it some other way.

And of course that "some other way" part of things is where you wind up getting hurt, following directives given by people who do not know what the hell they're talking about.

The ropes are fine, as-is. They never fail. Nobody ever falls. EVER.

The wooden platform of the float itself is fine, as-is. They never fail. Nobody ever falls. EVER.

And the whole system is fine, as-is. It never fails. Nobody ever falls. EVER.

Do you really think you know more about what Dave is doing than Dave knows about it himself?

Really?

My guess is that Dave would laugh right out loud in your face if you tried to tell him something like that.

In. Your. Face.

Dave's not getting on the sonofabitch unless and until DAVE considers it fit and proper for the purposes of holding him up, mid-air, in an otherwise completely unreachable location, in a way that can be guaranteed to keep him safe while he's up there.

So get a good gander at what works, maybe. Try to learn from what you're seeing, maybe.

It looks light, and it is, but it's plenty heavy enough, and that lightness translates directly into ease of setting it up, getting it into place, and just generally being able to manipulate things, in the safest manner possible.

And it's also remarkably simple, and easy to understand, which makes for a vastly better and more-complete grasp of things, with less crap to have to consider, when you're giving it the looking-over it gets every time before it gets used.

And it also makes for less bullshit to have to go through as you're setting it up, which makes for less time spent and less work done, which of course are yet more very good reasons for doing it this way.

Don't cost much money, either.

So ok. So this is how it's done. By the people who know how it all works, better than anybody else in the world.

And as for the absurd "safety line" around Dave's waist, that thing is strictly "eyewash" and beyond keeping somebody from raising a howl over it, it really has no proper function.

The ironworkers, with certain very specific instances and exceptions, didn't have much use for "safety lines" either.

Just another goddamned thing to get tangled up in, or snagged on in a hidden place, with a very real potential for hurting you or even killing you, and if you're not comfortable getting around up here without one, maybe you shouldn't be up here in the first place?

I recall more than one battle, with different Safety Departments, in different organizations, on different launch pads, and it was a huge pain in the ass. Every. Single. Time.

People with soft skin, in button-down shirts and well-polished shoes, sitting behind desks, issuing directives about safety lines, safety harnesses, and safety god-knows-what-else... none of which any of them had ever used for themselves, or had the faintest idea as to how it really worked, in the real world, up on the iron.

And they would dig in their heels, and we would dig in our heels, and the paper would fly, and the meetings would be held, and the ironworkers would just ignore the stupidity of it all and go right on getting it done, doing it right, and...

Ye gods! Parts of the job were no fun at all.

Somewhere, in the fetid air down at the very bottom of it... I can smell lawyers.

And of course everybody knows that there can be no better possible judge of what's safest, and what works best, up on high steel, than a goddamned lawyer, right?

Feh.

Ok. So what's going on with the tower in this image?

I mentioned modifications work for the OMS Pods Heated Purge Covers a little while ago, so let's familiarize ourselves by taking a closer look at some of that kind of stuff, ok?

We've already met the Orbiter Mold Line in several places, some high and some low, and we've been exposed to how it dictates the shape of the steel at the edges of the platform framing in the areas on the RSS that abut the Orbiter (or very nearly abut, since nothing actually touches the orbiter), but despite the fact that we've already encountered some bizarrely-complex aspects to it, we still really haven't fully plumbed the depths of this stuff yet, and our photograph up at the top of this page is one of the very best looks at one of these areas, so let's dig down into it for real, right now, ok?

Just to review, let us return to a 79K04400 Pad A drawing (Mind the elevations, and we're using the A Pad drawing to show you these curves because we don't have an equivalent drawing for Pad B, but it's the same places, ok?) that uses a little Descriptive Geometry to show the Orbiter Mold Line at each end of the Payload Bay, just as a reminder of how tricky these curves really are, once you actually have to break out the torches and clamps and welding gear down on the shop floor, and make the goddamned thing, starting out with steel shapes, that you get from the steel mill, board-straight, ok?

For these two areas only, they give us the curve in exquisite detail, and that's because in these two areas, only (well... excepting the Side Seal Panels, but they're straight as an arrow, having no curve to them at all), something will be touching the Orbiter, and even though it's only a very light and delicate Inflatable Seal, they still wanted to be damn good and sure they got the shape of the thing, exactly right, and so they went the extra mile with it, and produced these drawings with the curves nailed down, so that there could be no chance whatsoever for a mistake in this area.

But of course there's a story. There's always a story, right?

In the beginning... they weren't quite so sure about it, and so, not quite really knowing what the hell was going to be happening when their four-million-pound steel hotel came swinging around like a battleship to within a gnat's whisker of their multi-billion-dollar spaceship for the very first time, they decided to err on the side of caution just a little bit.

Observe.

This is the original Pad A incarnation of things down on the APU Servicing Platform at the 120'-0" level (mind those Pad A elevations), which is where we see Dave Skinner happily mugging for my camera in the photograph at the top of this page, at Pad B.

Let's zoom in on the drawing, to just the area we're interested in, showing us the floor steel in the area around the Orbiter Mold Line.

Where we discover, that originally, since they weren't quite sure about it, they specified that the floor perimeter steel at the Orbiter Mold Line be curved, in close agreement with the outline of the Space Shuttle's OMS Pods at this elevation on the tower, but they did it a funny way, with a note involving a different drawing, so let's go to the different drawing, and get to the bottom of the matter thereby.

79K04400 S-61.

And get a look at highlighted Note A, where it says "...compound curve in plan view. Exact dimensions will be furnished after award of contract..."

So clearly, when they were getting ready to build the RSS over on Pad A, they still hadn't quite decided on what to do with this stuff facing the Orbiter Mold Line down near the bottom of things at the APS Servicing Platform level and also at the APU Servicing Platform level.

Which of course didn't actually stop them, but it did put a little bump in the road right here.

All well and good, and however it wound up getting built over at A Pad (I was not around at the time, so I have no idea how it all went down), that's how it got built, but in the intervening period of time between my days on Pad B with Sheffield Steel, and my days on Pad B with Ivey Steel...

...things changed.

Slow-dawning realization that the Orbiter was not as robust, nor as safe, as they originally persuaded themselves to believe it was...

...was ever-so-creepingly beginning to set in, and with that creeping realization setting in...

...they also realized that they were going to have to modify things out on the pads to accommodate their altered understanding of their Space Shuttle...

...and this revealed itself to be a very dark hole, which, when they at first discovered it, and then ever-so-cautiously entered it and then began exploring it; and it expanded and branched out unexpectedly on them, into a bewildering labyrinth of ever-deeper side-tunnels and galleries which themselves continued to branch out in unexpected ways, growing and ramifying more and more, the farther they went down and into the clinging darkness of things.

And the whole thing was given a name, and that name was "Orbiter Weather Protection," and we're going to be going a pretty good ways down and into this very dark and very complex hole ourselves, but not all the way, because I left the Pad before it was all finally said and done with, and I did not participate in the culmination of things as they reached their final configuration, which final configuration wrapped itself around great tracts of both the RSS and the FSS and altered the look of the Pad mightily.

And so, right now, we find ourselves, looking at our photograph up at the top of this page, just dipping our toe into this very deep and also very dark water.

And what I just gave you is a bit of foreshadowing only, and soon enough we will be well and truly immersed in things, but for now, let us return to the Orbiter Mold Line down at the 125'-0" elevation on Pad B, and see how things came to take on the look you're seeing when you look at the photograph on the top of this page.

And please keep in mind that, as we ponder no end of very-curious-looking curves in certain parts of the floor framing down here, we're dealing with those curves because this is the area where the the RSS meets the Space Shuttle's OMS Pods, and those OMS Pods have a devilishly-complex three-dimensionally curved outline, and we're going to be dealing with it, as we deal with our steel in this area.

Here's what we're having to deal with.

And here it is again.

And once more, just to make sure you can really visualize this stuff.

They originally spec'd out those curves, over on Pad A, down at the APU Servicing Platform level, which is the second-to-lowest main level on the RSS, and below that, down at the very lowest main level of the RSS, on the APS Servicing Platform Level, and those very same curves made it over to Pad B, when I was there, working for Sheffield, and we can see the curve at elevation 125'-0", where Dave Skinner is working, as it was originally furnished an installed, in some of the photographs I took when I worked for Sheffield.

None of these images are particularly good for the purposes of showing you the curved steel that was originally furnished and installed on Pad B, complete with a Compressible Bumper on it, but it's there, and you can see it. Its main distinguishing feature is that, unlike the steel at the next level down, at 112'-0", as you travel along the curve toward the centerline of the RSS, the curve comes all the way around, and begins to double back on itself, and in the areas closest to the centerline of the RSS on either side, closest to where the Orbiter's Tail would be located, it comes to a very distinct and noticeable point.

We'll look at things again, on the Pad A drawings, just to make sure you can visualize it, and distinguish the APU Servicing Platform curved and "pointed" steel, from the very-similar, curved but "unpointed," steel below it, down at the APS Servicing Platform. Be sure to click the images to bring them up full-size, ok? The "points" on the curved steel at the APU Servicing Platform are not shown particularly well on the drawing, but there is clearly a noticeable difference between the elevations, once you're on to it, and once you know exactly what to look for.

Click the following photographs for full-size, and then look closely at the 125'-0" elevation (which by now you are presumed to be able to locate, on your own) in the Orbiter Mold Line area.

We'll start by looking up at it, from the ground.

And then we'll look down at it from above, even though it's almost completely incomprehensible, with a very obstructed view, but if we highlight it, we can see things with surprising clarity, especially the areas where the curve doubles back around on itself into a "point,"

And then one last time, from below again, but from nearby, looking up from the APS Servicing Platform beneath it, down at elevation 112'-0", where we can see part of it, directly beneath the folded-down Canister Access Platform and the guy handling the air line on the other side of the safety chains directly behind it, but not the part with the "point" on it.

So ok, so that's how they did it back in the beginning. What's the big deal, anyway?

And the big deal is that we're getting a near-perfect easy-to-digest, introduction into a hugely-complicated thing that wound up utterly altering the look of the towers. And which is a right bastard to understand the bizarrely-interlocking and extraordinarily-complex full details of.

And not only that, but by beating the living hell out of this thing down here, I'm also, sneakily, causing those of you who are actually clicking the links and attempting to understand (and of course everybody else jumped ship somewhere back in the middle of Page 1 and no, the rest of us do not miss them, actually), to build up some pretty good muscle memory as regards developing a sensible gut-feeling for what the place looks like down here. Which we're very definitely going to need as we plumb the depths, further and further into the world of Orbiter Weather Protection. Into the world of OWP, as it descends upon us from a starting point which is literally and structurally above the roof of the RCS Room.

And you've already seen it, but I'm guessing that none of you have actually noticed it...

...what?

The first hint of the coming OWP modifications down here. Down low.

And owing to the vagaries of history, and things that pass through the eyes of needles, we find ourselves having to flip back and forth between the Pad A drawings and the Pad B drawings, but, as if by a miracle, the very first alterations, down here at 125'-0", have been preserved, and we get to see them.

Back to the zoomed-in Pad A version of what it looks like down here at the APU Servicing Platform.

And now to the zoomed-in Pad B version of what it looks like down here at the APU Servicing Platform.

Anything kind of... catching your eye there?

Any... discrepancy maybe?

Open 'em both up in different tabs and blink back and forth between them.

And now you can see that the entire curved cutout area, the entire space that will be filled up with the OMS Pods when the RSS is mated with the Space Shuttle at the level of the APU Servicing Platform...

...has gotten MUCH larger on the B Pad drawing than it was on the A Pad drawing.

MUCH larger.

And if you look closely, you suddenly realize that on Pad B, it's not even curved anymore!

It's a series of straight C8x11.5 segments, and not a curve to be found, anywhere!

So what happened? What changed? Luck was very definitely with us when The Fates decreed that the changes that are manifest on the Pad B drawing, never got incorporated into the Pad A drawing. And we're closing in on another bizarre twist of fate regarding "what got incorporated into the drawings" as compared to "what did not get incorporated into the drawings"... but not yet. Not right now. But soon. Soon enough.

For the moment, we've been given a miraculous periscope into a long-forgotten past...

...where things were changing.

And we can see on the Pad B drawing, on 79K14110 drawing S-32, how they did it.

We can see that they eliminated the curve by cutting the floor steel back, and breaking the area where the enlarged curve would be, into a group of small-enough arrow-straight bits, called out a whole series of "rise over run" numbers for each bit, and wound up with a perfectly acceptable shape and avoided a whole bunch of over-fussy and over-expensive fabrication and erection bullshit in the process.

And then you go back to our photograph and give it a click to zoom it in full-size, and sure enough, every single bit of that Orbiter Mold Line steel which Dave has his left hand on, is straight segments of C8x11.5 welded together end-to-end and there's not a curve to be seen on any of it.

Makes perfect sense to me.

And our photograph serves as a sterling example of the fact that Ivey Steel hit the ground running, once they'd been awarded this contract.

This is only the second photograph in Part 2, and yet the floor steel at elevation 125'-0" had already been cut back and reworked, to an almost fully-finished configuration, before I ever managed to get up here with my camera for the first time and start taking pictures once again.

Compare this area with our very first image in Part 2, where you can see that this whole area remains untouched.

But it sure as hell didn't stay that way for very long, and here we are looking at yet another excellent example of just how fast Union Ironworkers get things done.

But why?

Why did they enlarge the cutout area down here at 125'-0" so much?

Did somebody come along and greatly enlarge the Space Shuttle's OMS Pods? And eliminate the curves which make up their overall shape and replace them with straight-line segments while they were doing it?

Of course not.

So what's going on here, anyway?

And it turns out to be the same thing that caused them to butcher the floor steel one level up, on the RSS Main Floor at 135'-7", even as they left the floor steel one level down, on the APS Servicing Platform at 112'-0" completely untouched.

And it turned out that they needed more room for the damnable OMS Pod Heated Purge Covers, down here at 125'-0", and farther up at 135'-7", but not farther down at 112'-0", and we're almost there...

...but not yet.

And this set of modifications is only the tip of what turned out to be a VERY large iceberg, and in addition to what we've seen so far about the need for more space that dictated they cut the floor steel back at 125 and 135 and rebuild it with a different configuration...

...there's a whole separate operational discipline, a whole separate element to things, represented by one other item of interest in our photograph, and I may as well deal with it right now, because this is by far our best image of that item, pre-modification, so ok, let's go.

And our item of interest is this little guy right here.

A hand-operated winch, painted red, mounted on a stub column which is not properly visible on our photograph, but that's ok, we can live without the stub column for the moment.

And it's part of the Canister Hoisting System, and it's surprisingly complicated all by itself, and what they wound up doing with it after our photograph was taken is also surprisingly complicated, and we're going to be taking a little journey.

And our photograph showing us the winch is an excellent starting point, and in conjunction with the drawings, I'm going to lead you along the pathway of the Canister Hoisting System.

And our little red winch was mounted on a peculiar back-to-back double-channel 8x11.5 support column that ties directly to the RSS Main Framing at its top, and the floor steel at its bottom, with an even more peculiar double WT 3x12.5 angled brace that came down from above, and met the double-channel column in the middle, right behind where the winch sat over on the other side of the column.

Like this.

And there were two of these winches and they worked in tandem, one on either side of the centerline of the RSS (and the centerline of the Canister when it was being lifted, too), and you go looking at that drawing again, and you realize...

...these things were pretty sturdy.

And very reasonably so, considering the job they had to do, pulling the Canister into line.

The wire rope that came off the winch did not go straight to the Canister, and instead went through an equally-sturdy double-sheave that hung down from above, in front of the winch, and it only went to the Canister after it passed through that sheave.

Here's the double-sheave.

And here's the attach hardware it used to attach to the top, and the bottom, of the Canister when they were using it.

Sturdy enough, I guess.

And its job was to steady the Canister, and to also guide it some, as they raised and lowered the Canister into position (using the 90-ton Hoist, which is VASTLY stronger), to a position where it's suspended against the face of the RSS and firmly locked down in that position, where they could open the PCR Doors, and open the Canister Doors, and then remove the payload(s) for the next Space Shuttle mission from the Canister, and get 'em all nice and hung on the PGHM, and then close the PCR Doors and the Canister Doors, before they took the now-empty Canister down to the ground, on its Transporter, which drove it away, and then they would swing the RSS around and mate it with the Space Shuttle (which had already been rolled to the pad), at which point the process would be reversed and the payloads being held by the PGHM would be rolled forward past the once-again-opened PCR Doors, and the now-open Space Shuttle Payload Bay Doors, and get placed into the Shuttle's Payload Bay, and then they'd roll the PGHM back and close all the doors and demate the RSS to get it out of the way, and they'd be ready to go fly.

And the Canister was BIG, and it was HEAVY, and when you're steadying or guiding or maybe a little bit of both, by yanking on something that's 65 feet long and weighs up to 140,000 pounds...

...sometimes it yanks back, and if it does, you better be ready for it, and of course one of the ways you be ready for it is to make all of your hardware that's involved with it nice and strong.

And that's exactly what they did with this stuff. They made all of it nice and strong.

And now for the journey.

Hold on to your hats, because here we go.

We will ignore what they did with the Canister when it was away from the Pad, ok?

Not part of my job description.

Not gonna get into it.

The put the payload inside the Canister, put the Canister on top of its Transporter, standing on end, and drove it out to the Pad, where they parked the Transporter beneath the RSS, and went to work.

Which is where we will pick up the story, ok?

And it seems easy enough on the surface of things, but then again doesn't everything?

Which of course is why idiots who cannot even run their own miserable and worthless lives successfully, blithely believe themselves capable of running the whole country successfully, even though they are... complete idiots. Or, more likely, because they are complete idiots.

And it's only when it's you that's sweating through the details of making something serious and high-risk happen, correctly, that the full complexities start to weigh down on you.

And when it comes to lifts, and heavy lifts in particular, oh hell yes you can bet your ass that no end of sneaky stuff (not such a small amount of which can be fatal if dealt with incorrectly, or not dealt with at all), starts jumping out of the woodwork at you, and you must account for all of it, or run the risk of suffering dire consequences.

And later on in Part 2, we're going to be seeing several nice pictures I took of the Canister for myself, but right now, we'll use some public-domain NASA pictures to show it to you, ok?

So ok.

So Payload Canister.

And its Transporter.

And as you can see in the NASA photograph just above, with the Canister beneath the RSS nicely lit up at nighttime, things start out simply enough with the Canister on its Transporter, plumb, square, true, and level, and every bit of that stands to reason, but it's what happens next that throws everything into a cocked hat, and causes people to have trouble understanding what the hell it is that they're doing, and why they would do it, and then everything that follows becomes equally murky and incomprehensible, and once again, I find myself as a lone voice crying in the wilderness, because nowhere can I find a simple and straightforward explanation of the whole operation, where all the weirdness is tied together to make it plain and simple enough to understand (and really, once you get the sense of it, it's pretty straightforward stuff, and plenty easy enough to understand by pretty much anybody), so, using the drawings that's exactly what I'm going to try to do here, ok?

And the first thing they do, once they're positioned correctly beneath the RSS (there's marks on the concrete to help 'em with that, just like the marks on the concrete at the airport where they park the planes at the gates), is to tilt the bed on the Transporter down in front, which then tips the whole Canister well forward, till it's looking like the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

Here's a picture of it on the ground, on its Transporter, tilted over, but there aren't really any good photographs of it, which show it tilted over clearly. Here's another one, and again, it's not so good, but at least you can see the Transporter "kneeling down" in front pretty well. And since these photos are none too wonderful, we're going to go to one of the drawings, but be careful, 'cause this drawing includes the Canister in FOUR different positions during the lift operations, and it can really throw you for a loop, if you're not fully aware, and I'm going to color it up to make it easier to understand, but even then, when it comes to the lines and rigging, it's still pretty tricky, so take it slow with this stuff, ok?

Here you go, drawing M-149, which is the general arrangement drawing, colored to show the Canister and Transporter in their initial positions, with the Transporter kneeling down in front, and the Canister tipped forward looking like the Leaning Tower of Pisa, just before they start pulling it up into the air, and in addition to showing you the Canister in 4 separate positions, it does so from TWO different viewpoints, one from the side (on the left side of the drawing) and one looking straight at it from behind, facing the RSS square-on (on the right side of the drawing), and yeah, it's nice that they've learned how to pack incredible amounts of information into single engineering drawings, but sometimes...

And why in the name of hell are they tipping that Canister forward like that?.

That doesn't just look weird, it looks dangerous.

Like they're risking tipping it all the way over and having it come crashing down to the ground.

So..... WHY?

Why do that?

And it comes down to some of that sneaky stuff I mentioned just a minute ago, when we're doing heavy lifts.

And maybe we'll introduce the subject by letting Michael E. Donahue of PRC tell you all about it.

And basically, that "kicking-out" which Michael just mentioned is a serious concern during heavy lifts, and when the load goes from being supported by whatever it's resting on, to being suspended by whatever's lifting it, you can rely on the fact that everything is never going to be aligned perfectly, and it's that imperfect alignment that you're always going to be dealing with that causes the problem, and the problem is that at the moment the load enters a state of free suspension, it's going to "kick" off to the side in some never-quite-exactly-measurable-in-advance way, and if you've got something big, and heavy, you better look out, because it just might go right through something as it potentially lurches off to the side, and if that's not enough, and if the "kick" is enough, it can start swinging like a pendulum, and all sorts of truly terrible things can then start happening, and... this is an issue with all heavy lifts of stuff that enters the lift without constraint, by freely-moving across the ground to wherever the pick is going to be made, which also has unique characteristics, each time, of differing precise weights and precise centers of mass, and our Payload Canister most very definitely falls squarely under this heading.

If you've ever seen video of a crane toppling over, it's often enough because the suspended load lurched off to the side as it entered its state of suspension, and just as soon as that happens, the whole center of gravity of the crane boom along with its suspended load has moved, and if it moves into a zone where the crane can no longer have enough counterweighted leverage to resist the power of the repositioned load pulling on it with huge force...

And people get killed.

And astonishingly-expensive equipment and material gets destroyed.

And this is serious business. Every time you make a lift.

And so, out on the Pad, they control for this as best they can by tilting the Canister forward to get its center of gravity, as close as they can, lined up with the Lifting Trunnions they hook on, up at the top of the Canister, and those are off center!

Why?

Why off center?

Why moved over to the side of things by a significant amount (go back to M-149 again, and take a closer look at the side view on the left side of the drawing, at the exact location where they're showing the lifting line connecting to the Canister) to a place that causes the Canister to hang in free suspension at a funny top-forward angle, with the bottom of the Canister leaning out, away from the RSS?

And of course more sneakiness with heavy lifts, and when you're in the middle of a lift, and the wind is blowing, even with tag lines (more on that in just a bit), your suspended load is going to be moving around some.

Well ok then, if it must move, how 'bout we fix things up so that the bottom end of our 65-foot-long 140,000 pound object is maybe a little farther away from our steel structure, than it might be otherwise? So it doesn't kind of, maybe, just a little bit, by accident, we didn't mean it, honest, bang into something on the way up?

Which is exactly what they do.

It's all about clearances and safety factors and forgiveness in case things take an excursion that perhaps we didn't want them to, and perhaps didn't expect them too, just in case.

And so they kneel the front end of the Transporter down, and jack the back end of it up, and the Canister tilts forward and they hook the big spreader beam that's being carried by the 90-ton Payload Hoist to the Lifting Trunnions that were, by design, placed off-center on the top of the Canister, and okey dokey, looks good to me, so let us proceed with things from here, ok?

And proceeding with things takes us directly to the Canister itself, because we're going be encountering things up on the iron that interface and interact directly with the Canister, which of course has it's own stuff for interfacing and interacting, so now it's time to go look at the Canister in a little more detail, and see what's what, with all that stuff.

So here's a .pdf file with a set of simple-enough drawings that give us a pretty good feel for the basic elements of the Canister as a whole.

And I'm going to extract one drawing in particular, giving us side views of the Canister, so you can more-clearly see what we're about to be getting into with this stuff, but be careful, 'cause they're pointing out the "Outrigger" but in fact, what they're pointing to is the Guide Shoe (hang on, we'll get to it, and it's important, so take note of it), which is supported by the Outrigger, which, strictly-speaking, is a separate thing from the Guide Shoe. So be warned, ok?

And then here's another .pdf file that gives us a really good written description of the Canister, and what's going on with it (and this is a really good document, and it's not too long, and I highly recommend you read it.

And now that we've read the document (We have, haven't we, hmm?), here's a labeled photograph showing us what's what, on the starboard side of the Canister, just like how I've highlighted it in the drawing, with the outrigger folded down.

And here's another labeled photograph, also showing the starboard side of the Canister, with the outrigger extended, showing us what it looks like with things ready-to-go, just about time to attach the lifting gear and "get up on it" and start the lift.

And now that we've just learned how our suspended load is going to move around some, while it's in the air... And it's not just the breeze doing that, either, sometimes it's the lifting lines. The wire ropes themselves, hanging down from the lifting sheaves and attached to the hook down at the bottom end of things, and those lines will sometimes, as they go from being free-hanging slack to being fully load-bearing the moment the load breaks contact with the ground, want to impart a little twist, or spin, into our suspended load, and we're going to need to keep that under control too, so, once again, there's a lot of sneaky stuff going on as we're lifting, and it's all wanting to do stuff to our suspended load that we do not want it to do, and so for these (and there's even more but let's give it a rest, shall we?) reasons, we attach tag lines to the bottom end of our load, to pull on it with, and keep it from going somewhere that we don't want it to go.

And we'll return to M-149 to see this, but I'm going to have to doctor it up some, or otherwise it's going to be way more confusing than we'd like, so kind of keep that in mind too, and as we proceed upwards with our lift (Remember the red winch in our photograph up at the top of this page? Remember that thing? We're eventually going to get far enough into our Canister Lift to be using that thing, which is the reason why we launched off into the very thick underbrush we find ourselves bushwhacking through right now, so hang in there, I'll tie it all back together, but we have a ways yet to go, before I can do that.) I'm going to be altering M-149 appropriately, at each step along the way, ok?

But first, here's the unaltered version of M-149, so you'll have it to compare with the altered version, and after working with the altered version a bit, you'll find that if you come back here to the unaltered one, it becomes much easier to understand.

So here we go with an altered M-149, showing us the Tag Lines they use to stabilize the Canister during the lift. And although it's still a little hard to visualize (especially that line coming off of Capstan 2 out of the plane of the drawing, in our direction at an angle, heading off to a distant snatch block setup which is sitting between us and the Canister as we view things with M-149, before it changes direction at the snatch block, now heading straight down into the plane of the drawing, down and over the end of the Transporter, and from there to the bottom of the Canister), but with a "ground level" view, we get a good feel for how the left and right Tag Lines, coming off of Capstans 1 and 3, can pull the Canister horizontally down on its bottom end to keep it from drifting and twisting (and to also maybe deliberately put a little drift and/or twist into it if we might ever need to). And oh yeah, we can kind of see how, when it comes to tag lines putting our desired horizontal forces on something, the farther away we get from the something in question the better (within reason, of course), because the farther away you get, the more horizontal the direction the tag line takes, from one end to the other.

And now we can look straight down on it from above, in plan view and see how Capstan 2 got moved completely out of the way, over next to Capstan 3, and we let the Snatch Blocks tie our Tag Line to the Canister, instead of doing it directly off the Capstan, like we do it with Capstans 1 and 3.

And the reason they couldn't put Capstan 2 out there in the middle of the Pad Deck, dispensing with the need for the snatch blocks, is because in order to get it far enough away, they wound up in the middle of the Crawlerway, and a Capstan sitting out there right in the middle of Crawlerway might not be such a good idea, when it comes time to use the Crawler to roll the next Space Shuttle out to the Pad, so they said, "Ok, let's put Capstan 2 over on the ground, right next to the base of the Hinge Column where Capstan 3 is welded on to it, and we'll use embeds in the Crawlerway and attach a pair of Snatch Blocks to 'em whenever we need 'em (and yes, owing to the ways in which running lines, that are under load, work with a load that's changing its position with respect to the snatch blocks, it needs to be a pair of snatch blocks), and that way we can work the Tag Line from Capstan 2 off of the Snatch Blocks and we'll be able to keep the Crawlerway clear for the Crawler, the next time we need to use it."

And now, finally, with the Tag Lines attached at the bottom of the Canister, and the big Spreader Beam which is hanging from the 90-ton Hoist Hook, ready to be attached to the Forward Lifting Trunnions on the top of the Canister, we're almost ready to lift the Canister.

Whatta ya mean, almost?

What the hell else do you need to be doing with the damn thing, anyway?

You're hooked on to it. You're hooked on to it all over the place. What the hell else are you going to be hooking on to it now? What else even is there?

And we've already been here before, back on Page 32 in Part 1 during my Sheffield Steel days, but at the time we had plenty of other fish to fry, and we did not get into it, but now we will, ok?

We're gonna get to use the Canister Access Platform. We're gonna get to walk the plank. But at least this time, there's going to be a great big Payload Canister out there to stand on, just off the end of the plank, instead of the shark-infested waters around a pirate ship.

And oh, by the way, while we're here, we also get a Bonus View of the Double-sheave Assembly that the wire rope coming off the Winch goes through, on its way to the Canister, complete with a bit of wire rope dangling down from where it's been reeved over the bottom sheave of the Double-sheave Assembly, but I'm pretty sure that's not the actual wire rope that goes with this thing, and is instead just a little something that the ironworkers tossed in there to give the winch and sheaves a bit of a functional test to make sure it actually works, after they installed it, 'cause the wire rope in this image has no fitting on the end. No open spelter socket with a detent pin on a lanyard, which is not the sort of thing one puts on as an afterthought, in the field.

And I even linked to the drawing for it, back on Page 32, and hit it with a little highlighting, and gave you the most cursory possible description of and for it, and then moved on and that was the end of that.

And please note, that from where I was located, as I took the photograph at the top of this page, I was almost standing right on top of where the thing had previously been located, prior to the hatchetings which the 125'-0" floor steel underwent in preparations for the installation of the evil OMS Pods Heated Purge Covers.

And we're gonna return to that same already-highlighted drawing again, but this time we're going to dig down a little deeper into this thing.

And we're returning to a drawing of a thing that no longer even exists in the photograph at the top of this page, because that drawing also, as part of letting you know how the Canister Access Platform works, depicts the Canister, unlike the drawing of the double flip-up platform that replaced it, and dammit, here I go again, ricocheting off into yet another only-partially-related-tangent, and I need to tell you that between my finishing of Part 1, and my starting in on the writing for Part 2, impossibly, as if by a miracle, the Long Lost 79K24048 Structural Drawings (some of the 79K24048 Electrical drawings had already fallen into my hands previously, and yes, you can find a very few of them sprinkled amongst Part 1, but they were not nearly enough To Tell The Tale), fell out of the sky, directly into my lap, and how in the name of all holy hell does this stuff just keep happening to me, anyway?

And the main point of this ricochet is to advise you that 79K24048 (which was produced by the Two-Headed-Monster of PRC/BRPH, which was a joint venture that was apparently concocted-up specifically for just this project), is, with just a very few exceptions, not nearly as good as what you've grown used to (and what I had grown used to also) with 79K04400, 79K10338, and 79K14110, all of which were done by RS&H, and all of which are much better in no end of obvious, and not-so-obvious ways. So fair warning, we're about to enter a realm where the engineering drawings are not as good as those we've grown accustomed to.

Phew.

Now... where were we?

Oh yeah, the already-demolished Canister Access Platform, which is depicted on a better drawing, which drawing we're about to use in order to understand how the hell did they lift that goddamned Canister into place, anyway?

Observe.

So we roll the Canister into position, get the Tag Lines on it, lower the Canister Access Platform down on top of it, walk out there on top of it, and from out there on top of it (Are you securely tied off with your safety harness and safety line properly and correctly in place? Don't step in the hole, ok?) we can attach the Lifting Gear from the 90-ton Hoist to the Forward Lifting Trunnions, including the integrally-attached 5-foot sling for the Adjusting Gear from our little red winch, which goes to a place on the Lifting Gear which we saw on the drawing that's just above the Trunnions. And then of course, once all that attaching is done, we get the hell off the top of the Canister and raise the Access Platform back up into its stowed and locked position where it's out of the way, and finally, the Canister is ready to go.

And here's the drawing once again, highlighted this time, now that you have a better idea of what you're seeing, and what it's for, that shows us what that looks like once it's all put together up there.

And just to review, again, ('cause it's tricky, right?) what we're seeing here on the drawing is that the big Cable Connectors to the Spreader Bar, the stuff that actually lifts the Canister, all 140,000 pounds of it, also have, integrally attached to them, five foot slings which we can then, once we're properly on the Lifting Trunnions, attach to our little winch. The red one. The one we saw in the photograph up at the top of this page. The one that started all this Canister stuff we've been talking about for just about forever now. And which we're still not done with.

Gah.

And now at last, the person with a nice clear view of things who's standing next to where the Canister Hoist Control Station is mounted, at elevation 125'-0" on the APU Servicing Platform next to the column out on front side of the RSS at Line B.7-3.4, who is controlling the operation of the 90-ton Hoist, is given the signal to proceed, and all the way up on top of the RSS, inside the Hoist Equipment Room, on its mount above the floor up there at elevation 212'-1", the Hoist Drum starts to turn... slowly... nice and slowly at first, and the lines go taut, and everything creaks and pings and maybe even pops a few times, and way down at the other end of the lines, directly in front of and below the person on the controls, the Canister comes to life, and starts moving.

And we're going to stop right here, and show you the scene, and we're going to use a drawing we've encountered before, back in Part 1 when we were up in the RCS Room, but this time I'm going to alter it, and I'm altering it for the same reason I altered M-149, because in it's unaltered state it's showing the Canister in FOUR places, so it's showing you too much, so I'm going to clean it up to give you a sporting chance of actually understanding what the hell's going on here, right at the exact moment the Canister comes alive.

And here's M-143 in its confusingly-unaltered state.

And here it is all nice and scrubbed clean (at least over on the left side where we're seeing things in "profile" view instead of "face-on", anyway) and labeled-up, showing you exactly what things looked like at the moment they put tension on the 90-ton Hoist lines, and the lift began.

Open 'em both up, in separate tabs, and flip back and forth between them, getting a feel for it. And while you're at it, maybe pay a little attention, in the unaltered version of M-143, to that lifting line coming down from the Head Sheaves up in the rafters of the RCS Room at elevation 238'-6", the one with the Cable Connectors down at the very bottom of it, which are what actually connects to the Lifting Trunnion on the Canister, and notice if you will, in that unaltered drawing, there seems to be TWO of 'em, and they're offset at an angle, just a wee little bit, and what's that all about, hmm?

In a minute. Hang on, ok?

And in our altered drawing, our little red winch (we already learned that there's actually two of 'em, and it matters, and I'm just about done speaking in the singular, which I've been doing so far, just to try and simplify a little) is right there, hooked on, and the half-inch cable coming off of it to the bottom of the big Cable Connector that hooks on to the Lifting Trunnion is drawn dead straight, like it's in full tension, but it's not. Right now, the line is just a whisker short of being completely slack, and it's supposed to be that way, and it's going to stay that way for just a little while longer, because they don't need to put it in full tension yet, and instead it's just sort of making sure things don't go trying to get away from them, and there's people all over the place on the platforming up there watching, each one with a specific thing they're tasked with making damn good and sure does NOT go wrong as the lift slowly proceeds, does NOT interfere in some way, and does NOT make Bad Contact in Bad Places, causing Bad Things to happen...

And the Canister's Guide Shoes, which are supported by the Outriggers, which are firmly fixed to the forward end of the Canister, start drifting straight up, closing in on the bottom of the Canister Guide Rails from beneath them, slowly, creepingly, but also irresistibly, and they do NOT want to get mixed up with the bottom end of those Guide Rails the wrong way.

And we have encountered the Canister Guide Rails a million times already, but above and beyond advising that it's important, I've never actually told you exactly what they do or how they work.

So ok, so here we go with the Canister Guide Rails, which we have just discovered, seem to work pretty closely with the Canister Guide Shoes.

And it's the Guide Rails that force the Canister into the correct position at every step along the way as it's on its way upward, by tightly-constraining the location of the Guide Shoes which are firmly attached to the Canister through the Outriggers, preventing it from swaying, or twisting, on the way up, after our little winches have been unhooked from it, and then, once it's all the way up, keeping it firmly fixed in place at the exact correct distance from the Payload Changeout Room, and the Payload Ground Handling Mechanism within it, and owing to the nature of lifts, and also the nature of rigging, although you might think you'd want to just set it all at the exact correct places to start with, and then just... pick it up, and be done with it, but of course that's not how things work, and that is how people who think they know, but don't, get themselves into real trouble when the real world comes knocking at their doors.

We've already covered the business of how large suspended loads will, whether you want them to or not, move around on you, and they can move in more than one way, and while they're in suspension, you must account for this, or face the consequences when it all goes horribly wrong on you. When you're doing your heavy lift outdoors, which we very definitely are with the Canister, the suspended load tends to be here or there, but it's never exactly here or there. It'll be close, and it may periodically pass through here or there, but it will never stay there. It never stops drifting around, even if only just a very little bit, but even just a very little bit can have terrifying consequences if it gets away from you.

And of course the Canister obeys all the laws of Suspended Loads, and they know it, and instead of shooting for impossible-to-achieve (and also very-likely-to-fail in some unexpectedly nasty way) false accuracy, they put a little bias into things, and with deliberate intent, they lift the Canister just a little too far away from the RSS. Just a little too far away from the PCR.

The centerline of the Lifting Sheaves on the 90-Hoist is "mislocated", slightly away from the RSS.

The head sheaves on the 90-ton Hoist are not even in the "right" place!

And even if the Canister hung with a perfectly vertical alignment, perfectly straight-up-and-down, with its Lifting Trunnions perfectly centered, it would still be in the "wrong" place, just a wee little bit too far away from the RSS.

And in so doing, they've fixed things up with the centerline of the Lifting Gear such that no matter what kind of excursion they might wind up getting, when they first start lifting the Canister, it's always going to be just a weency bit too far away, and right there is where our little red winches come into play.

They use those winches to tug on the Canister. One on each side. Working together. To keep the Canister from wagging around all over the goddamned place as the Guide Shoes are closing in on the bottom of the Guide Rails. The main Lifting Gear is all centered up slightly too far away, so whenever the Canister is exactly where it belongs, exactly where they want it to be, it's always going to be pulling against those winches. It's always going to be keeping good and sufficient tension on any winch lines you might be using to keep it exactly where you want it, as the force of gravity causes it to continuously try to return to its natural position, plumb, directly beneath the centerline of the Lifting Gear, which means the winch never goes slack, and they never lose precision control of exactly where the Canister is.

And they want to be doing this by pulling because there's no reasonable, practical, economical, or sane, way to push on the goddamned thing, and so they fix it up so as they'll always be in tension with those winches, and excursions bedamned, when it's time to get those Guide Shoes exactly where they're supposed to be, as they enter the very-confined opening space at the bottom of their respective Guide Rails, with sub-sixteenth inch accuracy if they want it, they'll work those winches like a virtuoso works a violin, to make it happen.

And yet another sneaky piece of interestingness occurs with the winches in tension, pulling on the Canister together. That tension not only pulls the Canister toward the RSS, but it also wants to center the Canister as it does so, too. So you wind up getting a little side-to-side control, just by virtue of exercising some front-to-back tension. Heavy lifts are funny things. There's a lot more going on with them than you might at first imagine.

And by god the Guide Shoes are going to enter the bottom of the Guide Rails, exactly where they're supposed to, despite the fact that we're hanging there in free suspension with nothing to keep us in place, and the Canister is sixty-five fucking feet tall and weighs one-hundred and forty fucking thousand pounds, and the wind is trying to blow it around all over the place (Are you gonna be the guy to impact the launch schedule by stopping the lift and telling 'em to wait until a calm day comes along with no breeze?) as you're closing in on the bottom of the Guide Rails with your Guide Shoes. And breeze or no, they make it happen. And of course, from there on up, the Guide Rails are there to keep things in line, so once they get the Shoes into the Rails, they unhook the little red winches, and "get up on it" with the big 90-ton Hoist.

And the whole deal kind of looks like this, with good old M-143 doctored up to show things with the Canister at the instant it breaks contact with the Transporter and goes into free suspension, and again once its up a little higher, with the Guide Shoe safely enclosed within the flanges of the Guide Rail, at the point where they're just about to unhook our little red winches, which once again have done a sterling job, and all's well in Shuttleland. And Canisterland too.

Just by way of a little more help in visualizing this stuff, here's a photograph of the Canister being lifted, and it's in an intermediate position between the two positions I just showed you on our altered copy of M-143, and it's very definitely off the ground in free suspension with the big Connecting Cables coming down off the Spreader Bar attached to the Forward Lifting Trunnions, and the Winch Lines are attached, too, but they're still slack, and the Guide Shoe has yet to reach the elevation of the bottom of the Guide Rail, and they're just about to pull it in toward the RSS using the Winch Lines to get it all aligned just so, but they haven't quite gotten to that point yet.

And now that you finally have a proper feel for just how touchy things are, with getting the Guide Shoes into the bottoms of the Guide Rails, take a look at our photograph from Page 32 (image number 033, Left OMS Pod Cutouts Area) once again, with a new pair of eyes, and that's an impossibly busy image, and I'm not going to torture you with it, and instead I'm going to alter the picture, too, to get rid of that whole PBK & Contingency Platforms mess, that's almost, but not quite blocking our view of yet another fascinating little detail regarding what we're dealing with here.

And here's image 033 without that whole PBK mess hanging out there off the front of the RSS and confusing the hell out of us.

And how about that! There sits the bottom of the Guide Rail! Completely unasked for. Viewed from a perfect direction to show you what I'm about to show you. Holy shit!

We need to stop. Right here. And consider.

How much more stuff is there, completely hidden in plain sight, that we've been blissfully unaware of as we've been going through all of these photographs?

It beggars the imagination.

And it also stands as a signal warning that we can be staring right at stuff for interminable amounts of time, and still never see any of it.

And then maybe stop to consider what else is sitting right there, hidden in plain sight, all around you, right now!

It can give you a cold shiver when you really think about it.

Ok. Enough of that. Back to the bottom of the Guide Rail in image 033.

Here it is zoomed-in on the altered photograph, image 033, with a label to tell you exactly where it is. Be sure and go back to the original photograph, 033, to compare things, ok? It helps a lot to have the context, and also know exactly what to be looking at within that context.

And when we were back there in Part 1, on a different page, Page 37, and we were looking down from the Left Vehicle Access Platform at elevation 191'-0", as part of my walking you around through things, I showed you a drawing which gives us the Guide Rail in pretty good detail, but I didn't really explain any of it, and without an explanation you cannot have ever been expected to actually understand all of what you were seeing, and what it actually meant, and now I'm going to take you to that drawing again, but this time our focus is on the bottom end of the Guide Rail, and the peculiarity of how the extreme bottom end of that W10x49 has been configured.

So here's M-79 again, highlighted to draw your attention to the bottom of the Guide Rail.

And now we know what they did to the bottom of the column, here's that exact same place on the altered photograph, nicely-labeled for you, to give you full understanding of the clipped flange at the bottom of the Guide Rail which they cut and ground off the hard edges of the steel around, to permit a more-forgiving horizontal entry of the Guide Shoe into the Guide Rail as the Canister is being pulled inward toward the RSS by our little red winch, after the 90-ton Hoist has temporarily stopped pulling it upward, until the leading end of the Guide Shoe is correctly and completely inside the mouth of the Guide Rail down at its extreme bottom end, at which point the lift can proceed upward once again.

Pretty radical, huh?

Who knew, this much stuff had to go on, perfectly orchestrated beneath the sky, out in the weather, every time they wanted to get that damned Canister into place up against the face of the RSS?

And of course, we're not even there yet.

We only just got the damned Guide Shoe into the far bottom end of the Guide Rail.

We're not done yet!

Ok. Now what?

Now it's time for the Canister to be lifted another sixty feet, roughly, until the Guide Shoes have reached the upper end of their length of travel along the Guide Rail, and it's time to get the Canister all nice and settled-in, up where it's able to do its job and disgorge its payload(s) into the innards of the PCR by handing 'em off to the PGHM.

And once we're all the way up, we're still not in a particularly stable configuration, because right now the 90-ton Hoist is all that's holding us up, and if you know what's good for you, you will never use a hoist to provide any kind of static support for your suspended load.

No.

Don't do that.

You're gonna kill somebody and tear the whole place up if you do that.

You must transfer the full weight of your suspended load from the hoist to a dedicated static support, and I don't care how good the brakes on your hoist are, and I don't care how good the locking pins on your hoist are, and you're going to transfer that load.

Period.

You go research this stuff if you want to. You go find out how things can go wrong when loads that are suspended for static operations remain suspended from devices that are solely intended for dynamic operations.

You're the guy who don't know diddly-shit about lifts. Not me. You go figure it out.

So ok, so how'd they do it?

And we very quickly discover that we've already been here before.

Back on Page 30 when we were poking around on the Antenna Access Platform down below the RCS Room.

And with the use of a few "normal" drawings, and a few heavily-doctored up drawings here and there, let us now look at things a little closer than we did before, now that the Canister is up here, and we're gonna need to transfer the load, and since we are now this far in, we may as well keep right on stroking, and give the whole 90-ton Hoist SYSTEM a good close looking-at so as we can really understand all this stuff.

So let's go look at the 90-ton Hoist.

And we've seen it a hundred times already, but let's look at it one more time, just to refamiliarize with it, and to do so, we'll use a delightfully-uncluttered and simplified Pad A electrical drawing of all things (Pad A... elevations... remember?) to look at it in "profile" and that way we can see all the main players, hoist, line, head sheaves, load block, and hook, without a bunch of other stuff cluttering the place up and confusing us. Be advised that the part of this drawing that we're looking at is much more of a "concept drawing" than an actual "as-built drawing", and for the moment, we like that, because even though each individual component isn't rendered exactly the way things wound up being furnished and installed out on the Pad, their overall sense, locations, and interrelationships are rendered perfectly.

So ok. So here's the 90-ton Hoist.

And here it is again, in its natural home, up on top of the RSS, on one of the Pad A 79K04400 drawings and... elevations.

Please notice, the hook as depicted on this drawing is not what we actually wound up with at the Pad. And of course this drawing was deliberately selected because of what's missing, and what's missing is the pair of Canister Stowage Link boom pendants, and the Spreader Bar that gets carried by the hook.

We'll return to that stuff pretty quick, but for now, it's easier to visualize things up here in the RCS Room without 'em.

So ok, so now a doctored-up drawing showing us what it looks like up here with the Canister still supported by the Hoist, and I'm very consciously and very deliberately removing the Canister Stowage Link boom pendants, because they're too-confusingly in the way, and they make it near impossible to see this stuff as it actually gets used, and I'm also removing the entire RCS Room Floor and Mezzanine Deck, too, for the same reason, and then on top of all that, I'm pasting in the Hoist Load Block from a different drawing, just to give it a bit more real-world fidelity.

And once all that gets done, here's what it looks like with the 90-ton Hoist holding up the Spreader Bar, which holds up the Connecting Cables, which attach to the Forward Lifting Trunnions, which the Canister is hanging from in suspension, ready to be handed off to the Canister Stowage Links boom pendants for static support.

And now that the Canister, and the Spreader Bar along with it, is at its proper final elevation, a member of the High Crew can tie off, and then get out there to where the Stowage Links connect to the Spreader Bar, remove the 5"Ø pin from the spelter socket (careful now, whatever the hell you do, don't drop that thing, 'cause it's heavy, and it'll go right through whatever it lands on), fit the spelter socket over the lifting lug on the Spreader Bar, and then put the pin back in it and secure the pin, and now we're ready to carry a load.

And the person down below on the Control Station for the Hoist is given the signal, and lets the hoist down, just a little bit, until, with a few more creaks and pings and maybe a pop or two, the Stowage Links are now bearing the entire load, and the lines from the Hoist Hook to the Spreader Bar have gone just a little bit slack, and now, finally we're ready to use those two goddamned stupid little red winches (the ones that started all this, remember?) down there at the bottom of things, and hook 'em on to the bottom of the Canister, and then suck the bottom of that goddamned Canister back in to the face of the RSS for once and for all, and get the damn thing locked in place, and now, "Mother may I?" can we get to work on our Payload? Please?

Yes you may, but I need to check your work with the Winches and the Stabilizing Braces before I give you the final go-ahead.

And before we go look at the Winches and the Stabilizing Braces, which are a surprisingly complicated (although everything with the Canister Hoisting System is "surprisingly" complicated, and when are we going to quit being surprised by this stuff, anyway?) set of ratchet turnbuckles, let's see what things look like up top, with the Stowage Links connected to the Spreader Bar which is still, and will remain so for the duration, holding up the Canister via the Connecting Cables hanging down from it to the Forward Lifting Trunnions, on the poor drawing that I continuously keep beating on, doctoring it up, which now has had the Hoist removed for clarity, in addition to all the other stuff I've previously wiped out.

And once all that gets done, here's what it looks like with the Canister Stowage Links holding up the Spreader Bar, which holds up the Connecting Cables, which attach to the Forward Lifting Trunnions, which the Canister is hanging from in suspension, ready to be sucked in to the face of the tower down on its bottom end, using our marvelous little red winches to do so.

Phew!

And here's the original version of M-143 once again, just so you can compare things as I've doctored them up, with the original, undoctored drawing, which is showing you what things look like, over on the right-hand side, with the Stowage Links carrying the load, and the Hoist still hooked on, slack, and the reason they leave it hooked on is because unhooking it is yet more work, and haven't we done enough already? And also, god forbid, if something was to go badly wrong with the Stowage Links (and don't go asking "How?", because it's enough to know that Murphy, and his entire team of lawyers, got there first, and they'll find a way if they can), we've got that Hoist all nice and hooked up too, and hopefully, please, it will keep that goddamned Canister and whatever (and maybe whoever) is inside of it, from going to the ground.

So we leave well enough alone with that Hoist hooked to the Spreader Bar, ok? It's doing fine, right where it is. Leave it the fuck alone.

Keep in mind of course, at this stage of the lifting operation, that the bottom end of the Canister is still sticking out away from the face of the RSS as it continues to dangle freely, held up only by its Lifting Trunnions, which Lifting Trunnions, please remember, are off center, and something's gotta be done about that with our Winches.

And here's what that looks like, on our good friend (doctored up yet again, a different way) M-143.

And for those of you have been following all of this closely, there should be an immediate question in your minds centered on the business of access.

As in, "If we used the Canister Access Flip-up Platform to give ourselves access to the top of the Canister to hook the Winch Lines on to the 5-foot Slings coming off the bottom ends of the big Connecting Cables that attached to the Forward Lifting Trunnions on the Canister, and now the top of the Canister is over 65 feet above us somewhere around elevation 198' in the lifted position in a place where the Access Flip-up down here at 125' can never give us access to anymore, how the hell are we supposed to take those same Winch Lines and get 'em connected to the BOTTOM of the Canister?"

Glad you asked.

I'll show it to you, and in this image, the Canister is exactly where I just showed it to you on the most-recent doctored-up version of M-143, fully lifted, but not yet rotated around to properly-vertical, still requiring the services of our Winch Lines to pull it in toward the RSS down on its bottom end. Same. Place. Exactly.

And of course that's no help at all, and it's going to need more than just a little bit of further elaboration, and as with everything else out here, there's a story inside the story, with yet another story inside of that, and since we're here, we may as well lean-in to it.

I previously mentioned about how radically the Pad got modified after I had departed, and what you're seeing in this image (and many other NASA public domain images, too) is showing things that bear no resemblance to what I'm giving to you in my own photographs as well as the drawings I'm using to help you understand all this.

You glance at this stuff, and yeah, ok, sure, it's not exactly the same, but it's close enough.

Maybe.

Maybe not.

And you start drilling down into things, looking closely, and all of a sudden, you discover that it's completely different, and a hell of a lot of what I'm talking about is nowhere to be seen on these NASA photographs.

And we've entered a zone where that is true to an extraordinary degree, and it will trip you up if you let it, and yes, things are very much so different, but even with those very extensive differences, the sense of the thing still stands, and the system, although altered greatly as the Pad continued to undergo extensive modifications over time, continued to operate in pretty much the exact same manner.

And down here in the lower reaches of the RSS, things changed, and one of the things that changed the most, is the whole APU Access Platforming area at 125'-0" and all the hardware that they're using in that area.

In fact, here's that photograph once again, the one with the Canister lifted, but not yet rotated around to fully-vertical, and ok... just you even find the 125'-0" steel. Any of it.

I'll wait right here for you.

Ok, how'd you do with it?

Did you find any of it?

Perhaps.

Perhaps not.

So ok, so let's dig in, shall we?

There's stuff going on down there that we need to know, and we're never going to know any of it until we can simply find it first.

And I'm going to go at our NASA photograph, to show you where stuff is, so that you can know it.

So once again, how did they get those Winch Lines on the BOTTOM of the Canister, anyway?

And we zoom in on our photograph to learn how.

And as with everything else around this place, once we start digging, we realize that what at first appeared to be more-than-sufficient size and detail, has now become insufficient, so I'm going to have to go at our zoomed-in crop, and not only make it larger, but also attempt to sharpen it up as I do so, so as the things that are plainly visible to me will become visible enough for you.

Make no mistake about it. It's a really good picture, and it's got everything, but it just needs a little help, ok?

So here it is, gone-at, much larger, with a bit of contrast and sharpening work applied to bring out just a little bit more detail in those places were we're going to be giving things a close look.

We'll start out by helping you orient yourself by showing you a drawing of the Canister Access Flip-up Platform, which got moved, and completely changed into a double flip-up, the actual "access" part of which, that you walk off the end of to find yourself standing on top of the Canister, is now attached to a small flip-up "bridge" platform that spans the gap in the 125' floor steel where the Orbiter's Tail will be when the RSS is mated to it (which will of course will need to be flipped up and out of the way when that happens). And even this is not strictly accurate and in full agreement with the photograph, because the floor steel shown in the drawing got completely chopped away and reworked at some point, and even the platform isn't the same, either, but enough already. Give it a rest! You can see what's going on here, and that's really all that matters right now.

And here's that completely-reworked Canister Access Platform in the photograph, with the "access" flip-up part of it stowed, locked in its "up" position, with the "bridge" part of it still in place, spanning the gap in the 125'-0" floor steel where the Orbiter's Tail will go, with the RSS mated.

And clearly, nobody's going to be trying to use this thing to hang a couple of wire ropes on the bottom of the Canister. No. Not gonna happen.

And this whole area down here at the APU Servicing Platform, elevation 125'-0" has gotten hairy, and my photograph fails to match NASA's photograph(s), and nobody's photographs match the drawings, and it's a hugely-complicated mess down here, so to maybe try and help you along a little more, I'm going to include another photograph courtesy of John A. O'Connor, which is a screenshot from a gigapan image, taken from what is without the slightest doubt, the world's best collection of images of not only this area, but all over the place, including the whole Pad, hosted at NASATECH.NET, and we're now looking "from the inside, out" at the same place I just showed you where I highlighted the "new" Canister Access Platform, and you can now see one of the two Winches, and it's no longer red, and it's no longer hand-operated, and it's no longer mounted on a stub column, and is instead, yellow, electric, and it's floor-mounted.

But it's the same winch and it does the same job.

It also does more now, lots more in fact, but it's the same winch they will be using to tie to the slings which hang from the bottom of the Canister, and they're going to be pulling the Canister in with it, and that's all well and good, but we still don't know how in hell they managed to get the damned winch lines on the bottom of the Canister! But you've got to give me time, ok? I will get us there.

Like I just said a minute ago, it's gotten hairy.

Part of the hairiness consists in the fact that the rigging, the lines they use to pull on stuff with, is completely different from what's shown on the drawings.

And it looks (I do not know for a certain fact, because I was gone before this final incarnation of things down here was ever designed, nevermind furnished and installed, and I therefore must surmise, with nothing more to go on than NASA's imagery, and John A. O'Connor's gigapans), that everything was done with a sling (or more likely more than one sling), which connected to the winch on one end, was reeved through a snatch block or two, someplace midway along its length, and then attached at its other end to whatever might have needed some force applied to it for lifting, lowering, or just pulling.

And I'm going to presume that there was a dedicated sling, having a single snatch block on it, which was used to pull the bottom of the Canister all the way back to the face of the RSS, and for the purposes of subsequent discussion, I'm going to call that presumptive sling the "Tugger Sling." And we all know I'm just making this shit up, and if this sling existed in the first place as a single dedicated-use piece of hardware, it surely had a different name, but... we're missing stuff. We wish we had just a little more information, but we do not, and in its absence, in order to keep sensible track of things, we're forced to use our own made-up nomenclature.